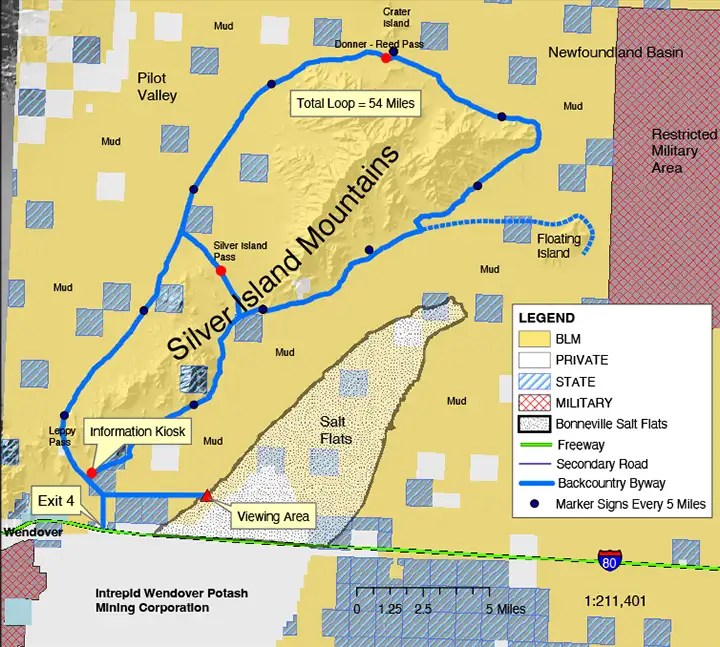

Bonneville Salt Flats

The Bonneville Salt Flats after a September rain

In 1827, Jedediah Smith was returning from his first trip to California when he came across what we now know as the Bonneville Salt Flats. He'd probably heard about it before from Native Americans he'd come across. Joseph Walker, another famous frontiersman, was mapping and exploring this area around the Great Salt Lake in 1833. As was the custom in those days, he named the salt flats for his boss: Captain Benjamin L.E. Bonneville. There's no record, though, of Bonneville ever coming to this place that was named for him.

John C. Fremont and his expedition went straight across the salt flats, looking for a shorter route to California in 1845. In 1846 his route became part of the Hastings Cutoff, promoted by Lansford Hastings as an easier (and quicker) route to California than the usual route through Idaho off the Oregon Trail. The Donner Party traveled this route in 1846 and troubles they experienced on the salt flats contributed greatly to their later misfortune high in the Sierras. Because of the Donner-Reed tragedy, there was never any extensive use of the Hastings route. Today, it is still protected as part of the California National Historic Trail.

The Bonneville Salt Flats cover about 46 square miles of land with a surface material that is about 90% pure table salt, the rest being mostly gypsum. In the center of the area, the salt crust is up to 5 feet thick, but that thins as you get out to the edges where the crust is maybe 1 inch thick. Because of the structure of that crust and the variances in seasonal water flow, the BLM manages the area as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern and as a Special Recreation Management Area.

In late spring and summer the heat evaporates any water in the area quickly and the salt crust gets very hard. In the cooler months, that water doesn't evaporate so quickly. For that matter, ground water often floods the salt flats up to several inches deep every winter. Combine that with periodic rainstorms and wind and you can see that the condition of the crust is constantly changing. That is what caused the problem with the Donner-Reed party: their wagon wheels broke through the salt and the time it took them to get their materials across the salt flats is what cost them the "season" and put them in the High Sierras short of rations at a really bad time of year.

These days, the Bonneville Salt Flats are most famous as the place where many land speed records have been set and then broken again. A lot of Hollywood producers also come here for filming purposes in this beautiful but stark, other-worldly environment. Because of concerns over the possible deterioration of the salt flats, the BLM has been working with a local potash mine to use their leftover salt (from the potash operation at Bonneville) in a brine mix that they then flood out onto the flats every year in late spring.

Bonneville Salt Flats, Silver Island Mountains in the distance