The Possible Supercontinent Vaalbara

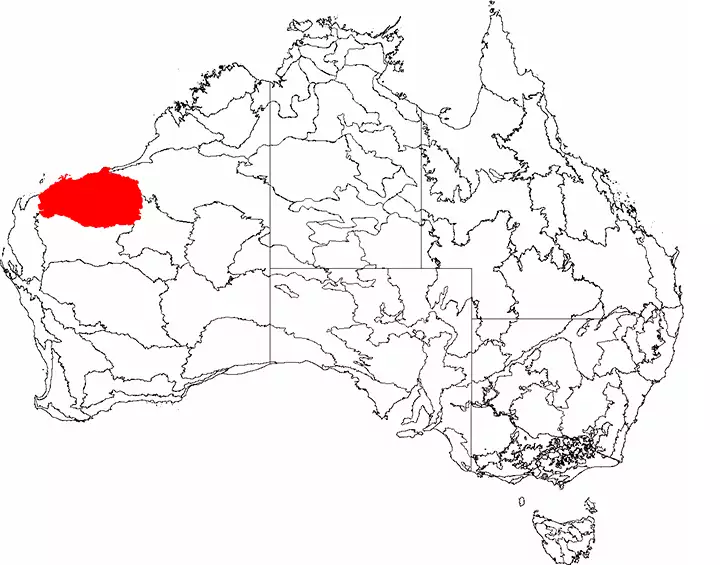

Location of the Pilbara craton today

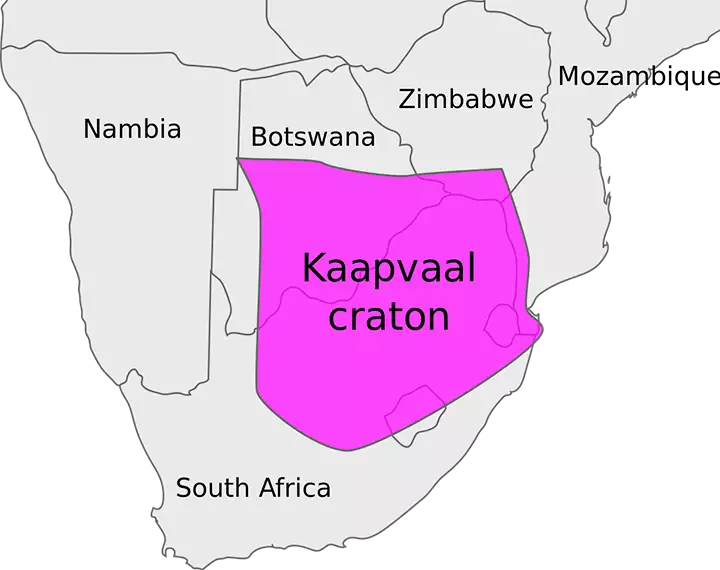

The supercontinent Vaalbara is postulated to have existed about 3.5 billion years ago, in the early Archean Eon. For geological evidence of Vaalbara, geologists point to the Kaapvaal craton in Southern Africa and the Pilbara craton in Western Australia (the name "Vaalbara" comes from the last four letters in the names of each craton). Paleomagnetic data recorded in the rocks of each indicate that about 3.8 billion years ago they were very close to each other. There are three lesser-known cratons in East Antarctica that date to the same time, share similar geologic history and were probably included in the land mass of Vaalbara.

Evidence also points to these cratons being close to each other again about 2.7 billion years ago. The supercontinent of Ur is postulated to have existed between Kaapvaal and Pilbara about 3 billion years ago and Ur underwent rapid expansion about 2.6 billion years ago when the two cratons were accreted to the edges of that supercontinent.

The Pilbara and Transvaal cratons contain some of the oldest rock on the surface of the planet. Contained in that rock are large amounts of well-preserved Archean microfossils. 2.7 billion year old shales on the Pilbara craton have yielded evidence of early photosynthesis.

The Kaapvaal and Pilbara cratons both show evidence of four large meteorite impacts between 3.2 and 3.5 billion years ago. Geologically, both craton areas also show faults in the Earth that were active about 3.5 billion years ago and show evidence of having been impacted hard about 3.5 billion years ago by something of extraterrestrial origin.

The Annandags Peaks on the Antarctic continent are a piece of Archean granite dated to be up to 3.9 billion years old. Uranium/lead dating of younger rock in the region gave a date around 3 billion years old. The tectonic-magmatic history was nearly identical in time and elemental makeup with the Kaapvaal craton, now in South Africa. In order for that to happen, the major cratons of the day had to be in close proximity to each other.

Geological evidence from the time of Vaalbara indicates that intracrustal melting and recycling must have been a major part of the early days of continent building. The planet must have been hot.

Today's location of the Kaapvaal craton